Nigeria has spent N46.62 billion on its flagship Ajaokuta Metal Firm over the previous decade, whilst the ability has failed to provide a single tonne of metal commercially, based on funds knowledge analysed by BusinessDay.

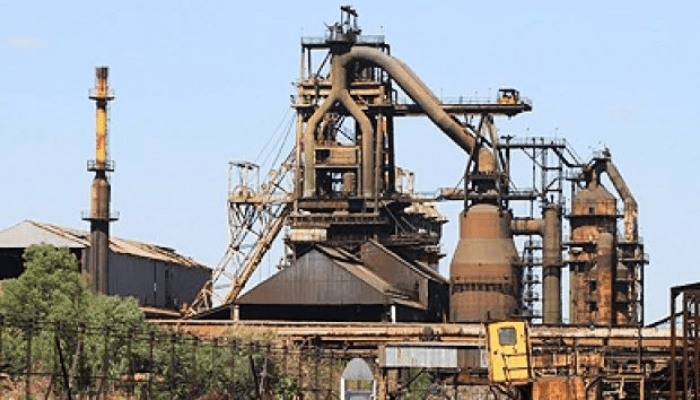

Conceived within the late Seventies because the flagship of an industrial revolution, the complicated was meant to anchor shipbuilding, development, transport, automotive, and manufacturing. As a substitute, it has grow to be a cautionary story of squandered billions, coverage flip-flops, and rusting infrastructure.

The spending sample, spanning 2017 via 2026, underscores Africa’s most populous nation’s battle to translate industrial ambitions into operational actuality. Regardless of repeated authorities pledges to revive the Soviet-era plant, annual allocations have primarily lined salaries, safety and upkeep relatively than capital enhancements which may allow manufacturing.

Knowledge sourced by BusinessDay from obtainable funds paperwork confirmed annual allocations to the dormant complicated have risen steadily, from N4.27 billion in 2017 to a projected N6.69 billion in 2026, the very best within the interval reviewed. The 2025 funds put aside N6.81 billion for a plant that successive administrations have described as essential infrastructure however have confirmed unable to operationalise.

Aisha Mohammed, an power analyst on the Lagos-based Centre for Growth Research, questioned the allocation technique.

“Spending billions yearly on upkeep with no clear path to manufacturing is fiscal irresponsibility,” Mohammed mentioned. “These sources might fund essential infrastructure that truly generates financial returns.”

Learn additionally: Nigeria wins €185.7m, N4bn arbitration over 1981 Ajaokuta steel contract

Business analyst Kayode Akintunde of Sofidam Capital famous the broader sample of failed state enterprises.

“Ajaokuta is symptomatic of Nigeria’s problem with public-sector industrial tasks,” he mentioned. “With out private-sector self-discipline and market incentives, these services grow to be employment packages relatively than productive belongings.”

Ifeoma Nwosu, a authorized analyst with expertise in infrastructure contracts, believes that unresolved litigation stays a significant purple flag. “Earlier than any severe funding can happen, Nigeria should clear the authorized slate. Buyers require clarity relating to liabilities, possession construction, and dispute decision mechanisms.”

On the technical entrance, Chinedu Agbo, a former consultant for Ajaokuta Metal Plant, acknowledged that some plant components are past restore.

“A lot of the imported Soviet-era machines had been by no means put in. Those who had been have deteriorated dramatically. Ajaokuta’s revival requires extra than simply repairs. It necessitates re-engineering from the bottom up utilizing fashionable know-how that meets in the present day’s business requirements,” he acknowledged.

The expenditures come as Nigeria grapples with a mounting debt burden and competing growth priorities. The West African nation’s whole public debt stood at over $100 billion as of mid-2024, whereas infrastructure gaps in energy, transportation and healthcare stay acute.

Kalu Aja, an economist who has visited the location, mentioned, “No Nigerian can go to Ajaokuta, see investments of greater than $8bn rotting within the African solar, and never cry.”

“Ajaokuta Metal is gone, enable it to die,” he mentioned on X, previously referred to as Twitter. “Construct new ones.”

Whereas Nigeria struggles to develop its manufacturing sector, Egypt and South Africa have a lot increased metal manufacturing charges. Egypt produces roughly 10.6 million tonnes of metal per yr, whereas South Africa produces 4.9 million tonnes, based on the World Metal Affiliation.

In distinction, Nigeria produces solely 2.2 million tonnes, counting on scraps and billets imported primarily from China.

Learn additionally: Steel ministry goes digital with enterprise management system

Viability questions

Nigeria’s richest individual, Aliko Dangote, whose industrial conglomerate contains cement and petrochemical operations, questioned the plant’s basic design.

“Ajaokuta won’t ever work,” he mentioned in an interview on September 15. “It was not constructed the best way a metal plant ought to be constructed. Even if you happen to full it, you’ll nonetheless want billions of {dollars} to make it aggressive.”

The billionaire’s evaluation displays broader private-sector scepticism about retrofitting decades-old Soviet know-how to compete in fashionable metal markets dominated by environment friendly Chinese language, Indian and Brazilian producers.

Worldwide Overtures

On the 2023 Russia-Africa Summit in St. Petersburg, Nigerian officers instructed worldwide audiences the complicated was “over 90 % accomplished” and central to the nation’s industrial rebirth. Gabriel Aduda, then-permanent secretary within the Workplace of the Secretary to the Authorities of the Federation, highlighted discussions with Russia-based United Firm Rusal (UC Rusal) about revitalisation.

“The second we try this, then you possibly can see income for each of us,” Aduda mentioned. “UC Rusal will make its cash, and Nigeria, in fact, will create jobs.”

Practically three years later, no binding funding settlement has materialised. Authorities sources verify Nigeria has since opened discussions with Chinese language corporations after Russian engagements stalled, although no timelines or monetary commitments have been introduced.

Some argue that privatisation affords the cleanest route out of the quagmire. Promoting the complicated transparently to a consortium with confirmed experience and deep pockets might shift the danger away from taxpayers and inject effectivity. The federal authorities’s function would then concentrate on regulation, infrastructure, and incentives relatively than day by day operations.

Critics warning, nonetheless, that poorly structured gross sales, such because the ill-fated Indian concession, can backfire, leaving Nigeria to foot big payments. Success hinges on openness, enforceable contracts, and an finish to political interference.